Reclaim the Beach - Honoring the Black Bostonian Reclamation of Civil Rights

In the midst of the repealing of diversity, equity, and inclusion policies and attacks on our ability to achieve higher education by the new federal administration under Trump, it is important to take heed of our present reality, use the tools passed down to us, and take collective action.

An upcoming community event called Reclaim the Beach aims to serve as a reminder of the legacy of Black Boston’s reclamation of civil rights. Hosted by Reclaim Roxbury, a nonprofit housing justice advocacy organization, the event will be at Carson Beach on August 9th from 12 to 4PM. It will provide a curated space for community-centered fun and leisure, while also encouraging dialogue about racial violence at Carson Beach in connection to the Black movement against educational inequality.

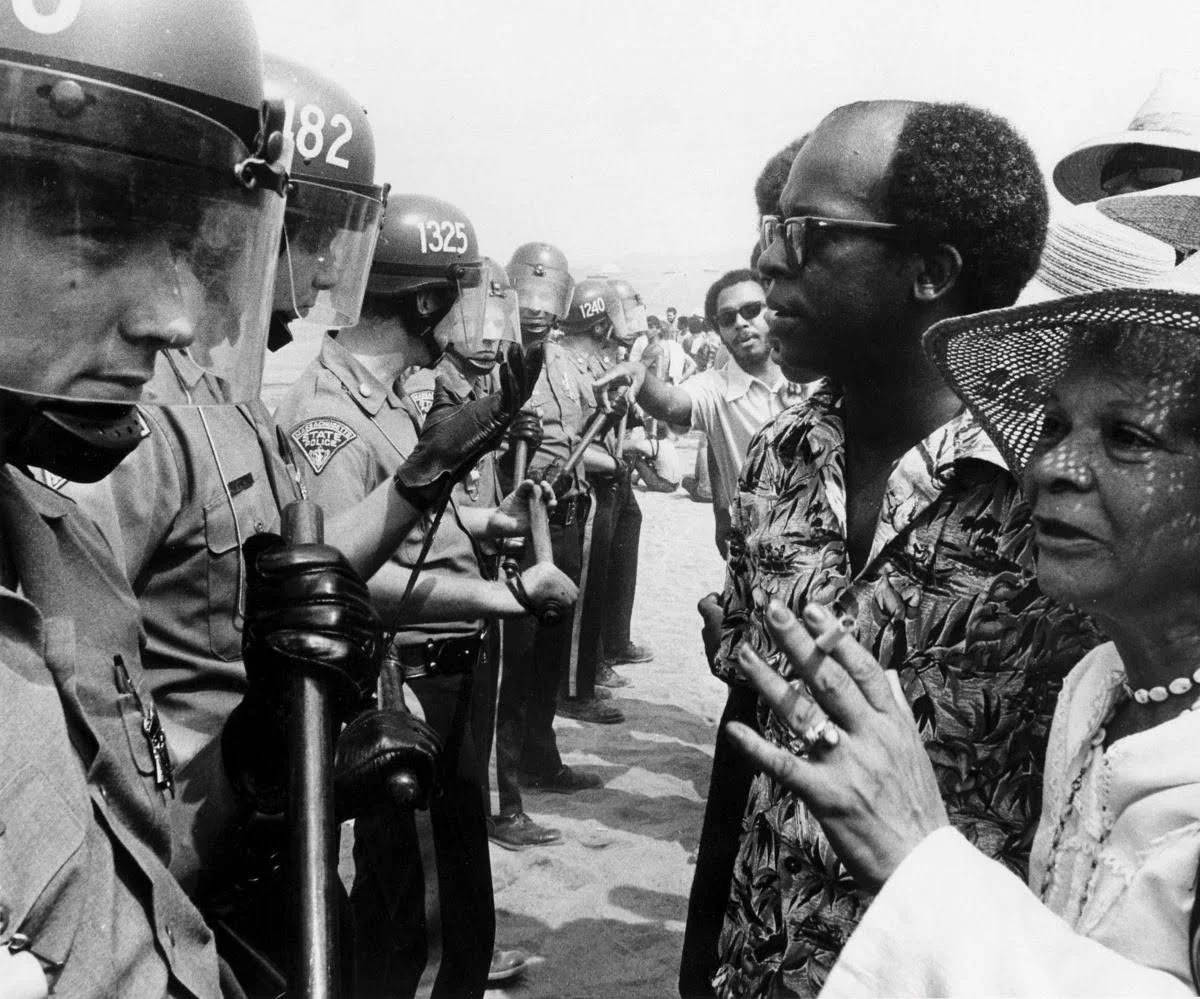

The President of the NAACP Boston Branch, Thomas Atkins, opposite of a police barricade at Carson Beach during the NAACP picnic demonstration against racial violence at the beach in 1975. Photo: The Boston Globe

Days after events of organized violence against Black beach goers at Carson Beach, Thomas Atkins, president of Boston’s chapter of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), along with several other leaders of Black civic groups called for a picnic at the beach on Sunday August 10th, 1975. Atkins stated that the purpose of the picnic was a reminder of, “the fundamental right of every citizen to use public facilities,” regardless of race.

The summer of 1975 picnic demonstration at Carson Beach was one of the many actions during Boston’s busing era that reaffirmed the right that Black Bostonians had not only to public spaces of leisure like the beach, but quality education as well. The fight against educational genocide was the foundation of the picnic action. Black mothers, youth, and civic leaders had long fought for quality education in the city of Boston.

This legacy is evident from the beginning of the 1950s and ongoing with the neighborhood of Roxbury at the center of it. The Roxbury community began to organize together, with notable leaders like Ruth Batson at the forefront, after becoming concerned about the low quality educational resources designated for Black youth. Together, they led the charge against the Boston School Committee's purposeful neglect of Black students within the Boston Public School system.

The Nurturing of a Movement

In 1963, Ruth Batson addressed the Boston School Committee as the NAACP Education Committee Chair, “We are aware of the problems confronting this school administration. We, like any citizens, are vitally concerned with good sound educational policies. Our demands tonight have centered around de facto segregation and its evil effects because we know that this issue has not been faced by Boston school officials. This issue must be dealt with, if we are to move along with the plans and blueprints that proclaim New Boston.”

As Black Bostonians endured exclusion from the Boston School Committee, they continued to organize marches, create schools with culturally relevant curricula, and influence policy. In 1963, state representative Royal Bolling Sr. introduced the Racial Imbalance Act, which was later enacted in 1965. The induction of the Racial Imbalance Act made Massachusetts the first state to ban segregation within its public schools.

This set the precedent for the class action lawsuit filed by the Boston Branch NAACP on behalf of 14 Black parents and 44 schoolchildren, on March 14th 1972. This lawsuit charged the city with consistently denying equal opportunities for Black youth within the Boston Public School system, by creating and maintaining a segregated educational system. Two years later on June 21st 1974, Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. confirmed that the defendant, the Boston School Committee, had intentionally performed and maintained a systematic segregation of Boston Public Schools. This was a historic decision, in which Judge Garrity demanded that the Boston School Committee, “Take whatever steps might be necessary to desegregate the school system.”

The Boston School Committee then took the “necessary” steps towards enacting the violent and ineffective busing period that shook Boston.

Picking Up Our Tools

In this remembrance of busing, I must note that Black Bostonians proposed community-centered alternatives. These alternatives included granting Black communities increased authority over predominantly Black schools along with the hiring of more teachers of color. In the end, these alternatives were rejected by white state officials and the Boston Teachers Union, who at the time could not fathom supporting a systematic framework of Black economic and educational control.

With the successful conclusion of Reclaim the Beach, it is important that we all take the time to educate ourselves and one another about the legacy of Boston’s Civil Rights Movement. For Black Bostonians, especially those raised by Roxbury, it is crucial that we recognize and act on the tools that our ancestors left for us to pick up and continue the fight.

One of many ancestors, Mel King, has specifically written for us to do so:

“At every point where we see people attempting to deny constitutional rights, whether it is the harassment of public housing tenants, or the denial of financial resources to people who want to remain in their urban home places, or assaults on visitors from out of town who do not know the ‘boundaries’ between Black and White territories, we must stand firm and insist that constitutional rights are protected. For every incident we allow to go unchallenged, we will find ourselves fighting dozens more.”